The challenge of mixed expectations

There are many stakeholders in the coaching environment that, depending on the context, include: parents; supporters; co-coaches; administrators; athletes; and specialist support staff.

It would be unusual for everyone to have the same expectations of the coach, who is usually the central co-ordinating figure. Often there is an expectation for the coach to have the answer, the silver bullet that will bring success and with it comes the pressure to deliver. Many coaches will feign knowledge rather than expose their doubts or shortcomings. Maintaining a façade of expertise can be exhausting, something requiring what is known to sociologists as emotional labour.

Certainly, the likelihood of conflicting agendas makes it challenging for a coach to act in a consistently person-centred way. If you have ever worked with a co- coach, at some stage you have probably wanted to do things differently to your colleague. If you’ve coached children, it is likely you’ve had to manage the challenging expectations of parents.

Research rationale

Having briefly identified some reasons why person-centredness is not straightforward, I would suggest, given the complexity, it’s OK to be imperfect.

However, it is not OK to accept our flaws passively with no intent to develop, and therefore having a clear understanding of what we are trying to achieve is important. So, is person-centred coaching about doing what athletes need or what they want?

As a coach developer, I have long searched for the best way to help other coaches behave in a person-centred manner, and for many years, the most helpful answer has started with ‘it depends on the context’.

At first, this seemed helpful. It was honest, offered flexibility and it resonated with many coaching stories I’d been a part of, where unexpected things had occurred.

Recently, I have thought more deeply and wondered whether there was something more useful and more consistent. Rather than searching for behaviours, is there a way to guide the intention behind a person-centred approach, that is independent of context and therefore constant?

What follows is a summary of my research into person-centred intention, which attempts to provide direction for practising coaches.

Research story

My research was conducted in Alpine ski coaching, where I studied both coaches and coach educators. Drawing upon expert delivery, I used video-stimulated recall to guide an interview process that explored the intention behind behaviour.

Analysis exposed strong themes that are useful in answering the question: how might we guide the intention behind a person-centred approach?

The POWA model

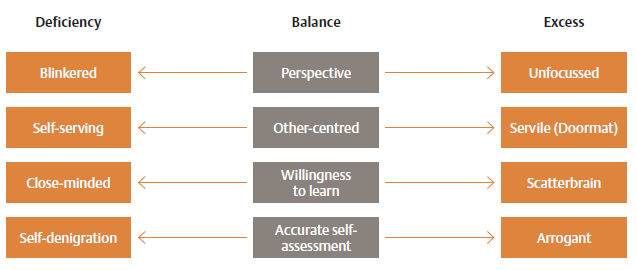

The four themes to come from this study that have been used to formulate the POWA model of person-centred intention are relevant to coaches regardless of their sport. The components of this model align with the concept of humility, to the extent that we can say humble intent is foundational for person-centred coaching. First, let us look at each component in turn, before exploring how the model can be used to support coaching practice.

Perspective

I like to view perspective using the metaphor of a camera lens. While it is often healthy to concentrate on the detail, it is also important to zoom out and consider the wider context. This responsibility often falls to the coach, especially when working with younger athletes who lack the maturity or experience to look across a season or number of years. Imagine the youth athlete who is cut from an academy programme – without perspective this could easily feel like a mortal blow. In addition to zooming out, we can change the lens entirely to see things from someone else’s perspective. The ability to manage our lenses in these two different ways is an essential mechanism for person-centredness.

Other-centredness

In the context of sport coaching this is about considering what the athlete needs as opposed to what feels convenient for the coach. The data clearly showed how other-centred intentions promoted autonomy-supportive learning, where the coach invested time and energy in creating interesting challenges to facilitate learning. Furthermore, there was an intentional social awareness that helped the coaches to ‘read people’ and an appropriate use of humour. Finally, the research showed this component to be facilitated by the other components of POWA and that in isolation an other-centredness does not necessarily lead to a truly person-centred approach. As an example, autonomy-support requires a willingness to learn from the coach, recognising there may be solutions to a problem that their athletes might discover before them.

Accurate self-assessment

The final component of POWA is perhaps the most difficult to apply. The emphasis here is on accuracy, which for some may require an acceptance that they do perform to a high standard in certain areas, and that they must overcome limitations of low self- esteem. For others it may require a recognition of inflated self-worth, an unpacking of why this happens and consideration for how it impacts others. Accuracy is one thing, but how and to whom we disclose this is another. Research shows that openly acknowledging one’s strengths should be motivated by an other- centredness and not simply to boost one’s ego.

The implication for the coach is that with accurate self-assessment comes a responsibility to adopt perspective, and to think deeply about how others will be affected by bringing these thoughts into the public domain.

So, to develop person-centredness you should reflect on your coaching and consider your position on each scale asking: “In which direction do I need to move to be more balanced?” Equally, for those of who are highly self-aware, and on top of their game, POWA is a simple enough model to use in the moment when faced with a coaching dilemma.

Should I intervene with this player or leave them to figure things out? How should I engage with this frustrated parent who is unsettling the learning process of my athlete? These everyday coaching dilemmas cannot always be resolved with a list of behaviours, as the right action will change almost every time and depends on the context. However, what should not change is our intention to be person-centred.

As we have already established, coaches are imperfect and will therefore at times find themselves unbalanced.

This unbalanced position might reflect an enduring trait or a specific moment, but either way the direction of this lack of balance is the important factor, and the subsequent solution that is required to rebalance. To help make sense of the model, here are some examples for deficiency and excess on each spectrum:

Blinkered – the coach who is only interested in seeing a change in performance in a session and who fails to consider the broader season.

Unfocussed – the coach who has no plan and fails to bring sufficient focus to drive a useful session.

Self-serving – the coach who is not prepared to deviate from their plan, even when they recognise the athletes need a different direction.

Servile – the coach who always says yes and panders to what athletes or parents request, to the detriment of their own well-being.

Closed-minded – the coach who is unwilling to take feedback or engage in new ways of working.

Scatterbrain – the ‘jack of all trades master of none’, who fails to bring sufficient depth to their work.

Self-denigration – the coach who lacks the courage to bring their strengths to positively influence athlete development.

Arrogant – the coach who wrongly believes they have solutions or who misreads situations whilst failing to reflect and apologise for errors.

We live in a world that is obsessed with self to the extent that the millennium generation have been dubbed “Generation ME”. Since the rise of positive psychology, we’ve seen waves of societal thinking that promotes an inward focus on subjective well-being and self-promotion.

I am passionate that we should strive to coach with more humility and consider the inherent hierarchies that affect coach-athlete interactions; adopt POWA as a model grounded in empirical research and bring more balance to your practice.

The POWA Model and Humility and Person-Centred Intention